Published in Culture Clash — a weekly column in The Tribune — on September 27, 2017

What makes you think you’re so smart? Maybe you got a few As and Bs on your national exams, maintained a decent GPA, got into your first choice university, landed a great job with a fancy title, or get a lot of likes on your lengthy Facebook posts.

Maybe your family members and friends pale in comparison with you. You’re a vessel of little-known tidbits, can recite excerpts of the classics, and play piano by ear. All of this could be true while you fail to effectively communicate because your emotional intelligence is undeveloped and, to be quite honest, you’re not even trying.

Emotional intelligence, according to Peter Salovey and John Mayer who coined the term, is “a form of social intelligence that involves the ability of monitoring your feelings and emotions and those of other people, discriminating among them, and using this information to guide your thinking and actions”.

In her book E.Q. Librium, Bahamian EQ practitioner and executive coach Yvette Bethel points out that the definition makes a distinction between feelings and emotions, and it’s an interesting one to explore. In short, Bethel explains feelings happen anywhere in the body while emotion includes reaction to a stimulus and often involves ego.

In developing and practising emotional intelligence, it is important for us to think about the ways we navigate feelings and emotions, or the way they can affect the way we navigate the world. Our responses are informed by our own lived experiences, values, and beliefs and affected by our mental and emotional states at the time.

Key to cultivating emotional intelligence is empathy — the ability to experience the emotions of another person. In order to communicate with emotional intelligence, we have to be able to relate to the audience’s conditions. This requires not only an understanding of who is in our audience, but how they feel. This knowledge has to be factored into our messaging for communication to be effective.

In a video circulating on Facebook, a child is shown trying to jump a barrier as classmates look on. Again and again, he runs up to it, and gets his hands on the top, but doesn’t quite make it over. With every attempt, his classmates cheer wildly. When he doesn’t make it, they shout words of encouragement. By the penultimate attempt, he is in tears, but his classmates’ cheers are only getting louder. Before the last try, they encircle him, building his confidence back up. When he makes it, it is a shared victory. Not only have the children in that video been taught the value of community, but to practice emotional intelligence. They know what failure feels like, and what people need to keep going, and to eventually succeed. They give that to the boy in the video without tiring, counting cost, or changing their energy. It is their job to support him.

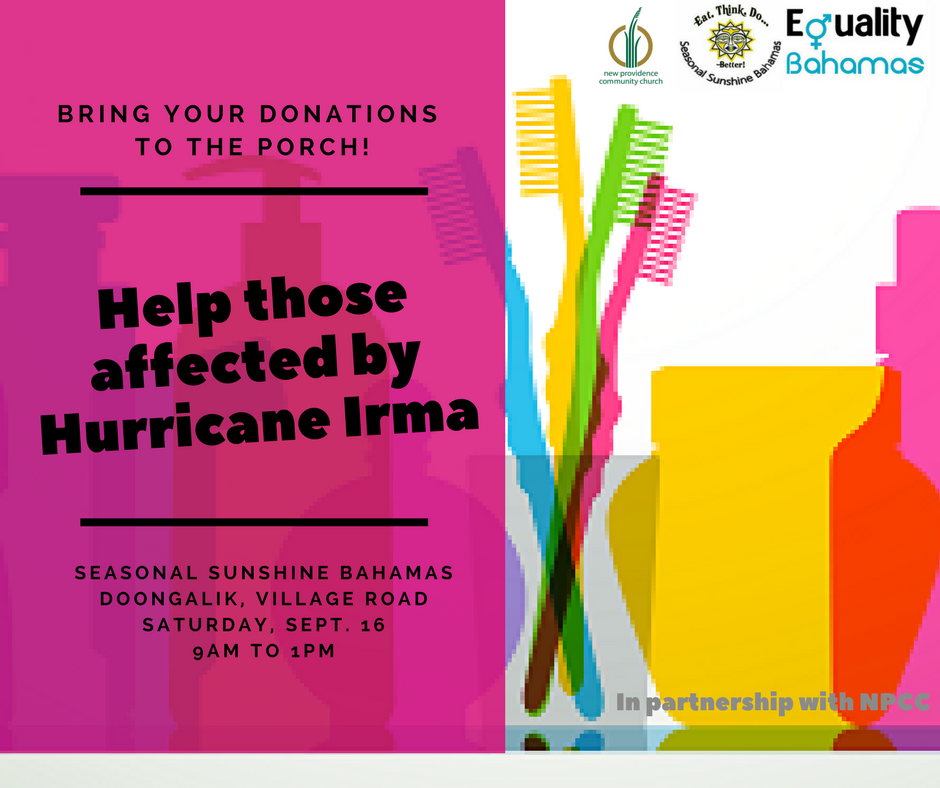

Just weeks ago, scores of Bahamian people were evacuated from the southern islands of The Bahamas under the threat of Hurricane Irma. Some refused to leave and, upon receiving this information, many Bahamians lambasted them. They were called foolish and uneducated, and some people even wished the worst, supposedly to teach them a lesson. This kind of response is quickly recognised as unchristian, but there is no need to connect it to religion. It is a character flaw that leads to communication failure. It is evidence of the inability to manage one’s own emotions — like anger or frustration — and the failure to consider the emotions of others.

Maybe it is difficult to imagine living on a Family Island, vastly different from the capital, and content with what one has while happy to be without certain elements that come with “development”. It’s easier to think of our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents who are reluctant to leave their homes.

The people we offer to take on trips, host during renovations, or bring into our homes when they are not feeling well. They decline every time because they love their homes, their independence, and the little things around them that make them feel at peace.

Somehow, even if we don’t quite understand it, we’re able to respond with love to these people who will not even go a 20-minute drive away, but can’t temper our frustration with people we think are foolishly, wilfully putting their lives at risk. We don’t bother to see it their way, understanding the deep connections they have with their homes and the fierce will to protect them, come what may. We are too busy making our own point.

This week, the prime minister announced, without much detail, plans to accommodate Dominican students affected by Hurricane Maria as soon as possible. We have seen evidence of the devastation in Dominica where even accessing clean water is a challenge.

The response to this announcement, just two years after Family Island students needed to be relocated to attend school, has been severely lacking in any kind of intelligence. People immediately asked where the money would come from, where the students would fit, how many people would be coming, and how long they would be permitted to stay? These are valid questions on the surface, but the tone is clear.

Many are opposed to this move and choose to hide behind faux-intelligence, prudence, and “critical” thinking. No one batted an eye when Dominica gave $100,000 to The Bahamas following Hurricane Matthew in 2016. No one bothered to make a GDP comparison between countries. It was fine for Dominica to help us, but we are too poor and under-resourced to offer assistance now. Maybe we are rich in fear and poor in community spirit, no matter how we try to spin it.

Minnis’ announcement seemed hasty, especially without having details of the plan to share, but there are better ways to pose questions and offer recommendations. We can have critical, constructive national dialogue without rejecting a plan we have not seen along with the people it is meant to help. To do that, we would have to acknowledge our own feelings and emotions, admitting to our fear of losing what we have.

We are most concerned about job security and the national debt and subsequent increases in taxation. While these are valid concerns, in the near future we will have to turn our attention to our shrinking land mass and rising sea levels, inability to save ourselves, and the need to build relationships with other countries who can lobby for and with us.

We will be looking to other countries in this region to band together with us in the fight for “developed” nations to do their part to mitigate and respond to climate change.

At the current rate, the next generation of Bahamians will be climate refugees. If we held and understood this knowledge, perhaps it would trigger the empathy we need to respond to Dominica’s situation and our prime minister’s commitment with emotional intelligence. No one wants to need help, much less to receive a protested offer.

We all have feelings, and experience emotions in response to our environment and experiences. We do not all practice the emotional intelligence necessary for leadership, community-building, advocacy, and critical dialogue. Communication is key to all of them, and dependent on our ability to reach our audience and be understood.

If we are not considerate of others’ emotions, we risk our messages — however articulate, factual, or relevant — being completely missed or ignored. If you find yourself under fire for comments, resist the urge to defend with “what I meant was” and spend time answering “How was I perceived, and why?” Impact is more important than intent, and emotional intelligence goes a long way in bridging the gap between the two.